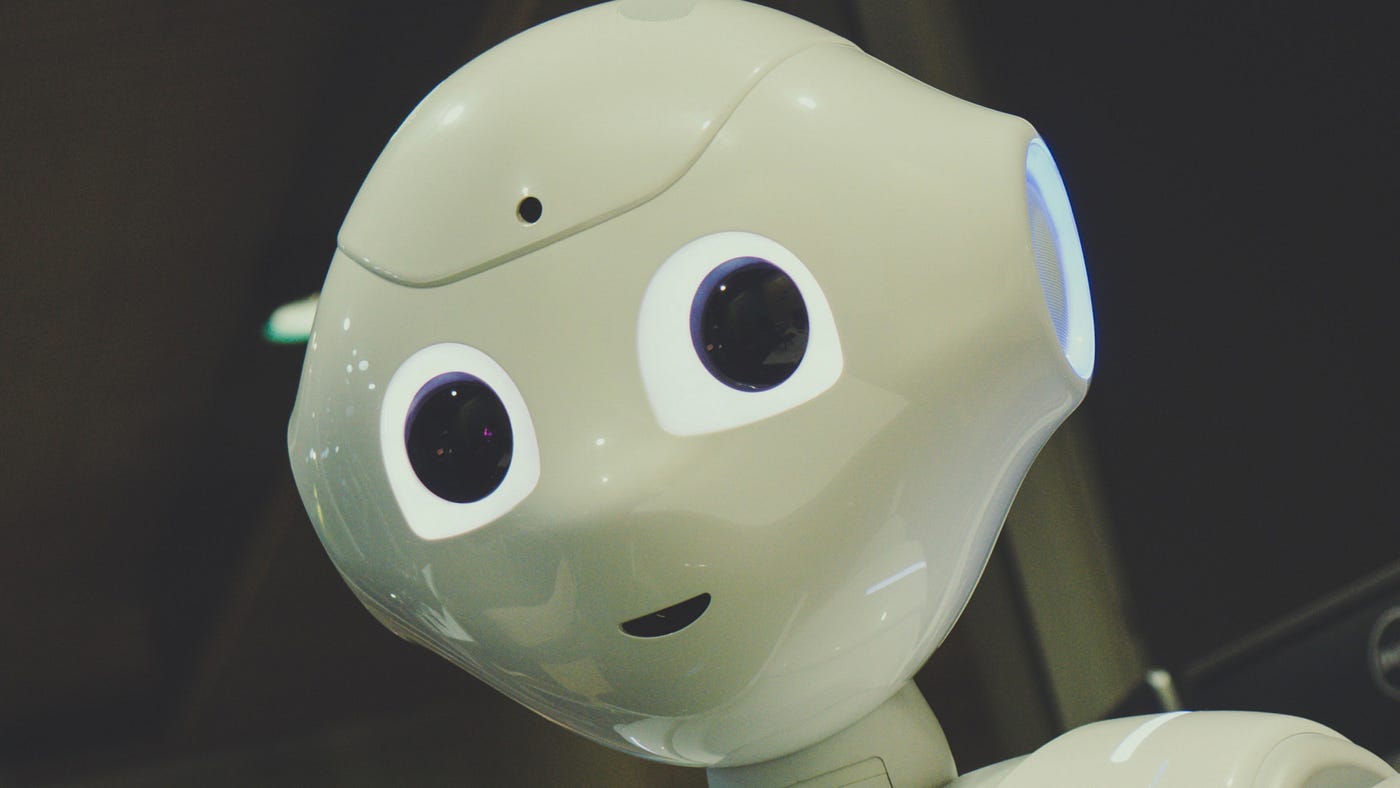

Does AI mimic humans? Or do we mimic AI?

Imagine that, in the not-too-distant future, machine learning algorithms spit out movies instead of text or fanciful paintings. What is a movie, but a series of images? The training data is a subset of all the movies ever created, labeled with ratings from the target audience.

An algorithm like that can churn out movie after movie after movie for very little marginal cost. It will be a very good time to be a movie company. And a very bad time to be a human working in the movie industry.

From the movie-goer’s perspective, however, what is the real difference between that hypothetical reality and our current one, except for scale? How many Star Wars movies and shows will come out between now and 2030? And how many billions of dollars in merchandising will they sell? Today’s movie companies don’t just produce movies — they engineer them. An algorithm like the one I described would just let them do so more efficiently.

Culturally, we’ve already accepted the premise that underlies such technology: movies are for entertainment, for stimulation, for hype, and then (maybe) some post-watch analyses — just so you know where all the Easter Eggs are. Many viewers, it seems, just want to see the same genres, the same characters, the same “universes,” the same brands, ad nauseum. To give them “same” more efficiently is just good business sense.

There’s another technology like this that already exists: automated essay feedback software. This is software that takes an essay written by a student and gives feedback to that student on how to improve their writing in their next revision.

The argument in favor of incorporating this software into the classroom is straightforward:

- Students need lots of practice writing essays to get good at it and existing research suggests that they don’t get enough practice.

- Essays, however, take forever to grade. And, generally speaking, teachers don’t have enough time to grade all these extra essays (or essay revisions) that students need.

- Therefore, automated essay feedback software helps students get the practice they need without increasing teacher burdens.

Teachers spend a lot of time giving students “low-level” feedback. “Tommy, you used the wrong verb tense, for the hundredth time.” “Samantha, could you possibly use a different conjunction than ‘and’ to make your sentences more interesting?” The software is pretty darn good at that — think of a souped-up grammar-checker.

The real goal, however, is for essay software to evaluate arguments — does the essay make a convincing argument? Does it support its claims with appropriate evidence? Is there a logical connection among its claims? Whether such software can adequately identify these more qualitative features, however, depends. If the algorithm has looked at thousands of graded essays for the same essay prompt, then it probably does alright. If not, then the problem becomes very hard.

Fundamentally, the drawback is the same for automated feedback software as it is for any machine learning algorithm: it cannot “know” what it has not “seen”. Our movie-making algorithm does not interpret the movies in the training set. It is not working from a cognitive model about what good or bad movies are. It’s just creating something that matches patterns in the training set. Automated feedback software will not recognize “good” essays that deviate from good essay patterns that it identified in the training set. And it will not recognize “bad” essays that cleverly match good essay patterns with nonsense.

But the existence of this software raises an important question: what are movies and essays and art of every kind fundamentally about? Is it about the object that is made — the movie or the essay or the piece of artwork? Or something else?

What if I told you that the essay you’re reading right now was created by an algorithm? No human wrote this. It is a collection of words meant to mimic other collections of words — a Furby that appears upset because you turned it upside down.

What if every piece of art you see — every movie, every book, every essay — was created by an algorithm? They’re still entertaining. You can still gain insight from them. Aren’t the objects themselves just as beautiful, just as interesting, just as valuable?

I don’t think so.

An essay is an act of communication between one intelligence to another. Remove the human reader from the equation — or the writer — and it’s just a paint-by-numbers exercise. A movie is an act of expression from one person — or group of people — to another. An AI-created movie does not express anything.

Essays are not just information-processing transformations. We write essays to advance conversations. An essay written to no one but a grading algorithm cannot be a part of the social conversation. So its grammatical correctness is a moot point. A movie patterned on other movies (even good movies), is just a confection — like gambling, a way to be entertained by randomness.

Ambitious filmmakers don’t want to make another kung fu movie — they want to make the next kung fu movie — the movie that advances the conversation about what kung fu movies are and can be. It is not just arbitrary recombinations of elements, ad infinitum.

Often, cautious futurists warn us of how AI, or other sophisticated technology, could adversely disrupt society. In this case, however, the cultural change precedes the technology — it’s not culturally “disruptive” technology — it’s just technology that furthers existing cultural norms.

Essay writing in most American schools is a paint-by-numbers exercise. To succeed on AP exams, students conform their essays to an expected form. Movie-making — at least big-budget movie-making — is also. Those aren’t the director’s grubby fingers you’re seeing on the film; it’s a Frankenstein patchwork of producers’ fingers.

If you want to be a brain in a jar, then by all means, stay entertained and informed by automated algorithms. But if you want to be part of a conversation, then you actually have to interact with other humans.

Member discussion